Impact of early complete molecular remission in allogeneic transplanted Ph+ ALL patients

-

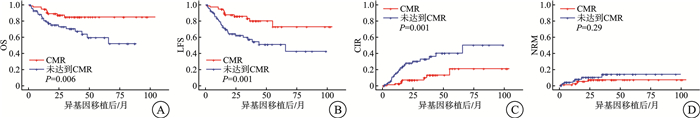

摘要: 目的 研究完全分子学缓解对使用异基因造血干细胞移植治疗的费城染色体阳性急性B淋巴细胞白血病(Ph+acute B-lymphocytic leukemia,Ph+B-ALL)患者的影响。方法 对2014—2021年在苏州大学附属第一医院血液科达到完全分子学缓解(CMR)后使用异基因造血干细胞移植治疗的147例Ph+B-ALL患者进行回顾性分析,评价其总生存(OS)率、无白血病生存(LFS)率、累积复发率(CIR)及治疗相关死亡率等指标,同时根据患者第90天时分子学状态将患者分为早期达到CMR组和未早期达到CMR组比较以上指标。结果 与确诊后第90天达到CMR的患者比较,确诊后第90天未达到CMR的患者3年OS率(85.0% vs 70.6%,P < 0.01)和无复发生存率(83.2% vs 57.4%,P < 0.01)均更低。在诊断后第90天未达到CMR的患者中,CIR更高(10.1% vs 33.0%,P < 0.01)。多变量分析显示,诊断后第90天未达到CMR是OS(HR=3.69,95%CI 1.48~8.71,P < 0.01)、LFS(HR=4.21,95%CI 1.84~9.64,P < 0.01)和CIR(HR=4.00,95%CI 1.60~9.99,P < 0.01)的独立危险因素。结论 早期达到完全分子学缓解是接受异基因造血干细胞移植的Ph+B-ALL患者获得较好生存的有利因素。

-

关键词:

- 费城染色体 /

- 急性B淋巴细胞白血病 /

- 完全分子学缓解 /

- 异基因造血干细胞移植

Abstract: Objective To analysis the efficacy of patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute B-lymphocytic leukemia(Ph+acute B-lymphocytic leukemia, Ph+B-ALL) treated with allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation(allo-HSCT) after achieving complete molecular remission(CMR) in clinical practice.Methods A retrospective analysis of 147 Ph+B-ALL patients treated with allo-HSCT after achieving CMR at the Department of Haematology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, from 2014 to 2021 was conducted to evaluate the overall survival(OS) rate, leukemia-free survival rate, cumulative relapse rate, and treatment-related mortality rate. At the same time, according to the molecular status of the patients at 90 days, the patients were classified into early CMR group and non-early CMR group to compare the above indexes.Results Patients who did not achieve CMR at day 90 after diagnosis had lower 3-year OS(85.0% vs 70.6%, P < 0.01) and recurrence-free survival(83.2% vs 57.4%, P < 0.01) compared with those who achieved CMR at day 90 after diagnosis. The cumulative recurrence rate(CIR) was higher in patients who did not achieve CMR at day 90 after diagnosis(10.1% vs 33.0%, P < 0.01). Multivariate analysis showed that failure to achieve CMR at day 90 after diagnosis was an OS(HR=3.69, 95%CI 1.48-8.71, P < 0.01), LFS(HR=4.21, 95%CI 1.84-9.64, P < 0.01) and CIR(HR=4.00, 95%CI 1.60-9.99, P < 0.01) of independent risk factors.Conclusion Early achievement of complete molecular remission is a favourable factor for better survival in Ph+B-ALL patients undergoing allo-HSCT. -

-

表 1 临床特征

例(%) 特征 数值 年龄/岁 ≤ 35 87(59.18) >35 60(40.82) 性别 男 77(52.38) 女 70(47.62) 染色体核型 单纯Ph+ 39(26.53) 合并其他染色体突变 96(65.31) 未知 12(8.16) BCR/ABL1转录本类型 P190 87(59.18) P210 38(25.85) 未知 22(14.97) 诊断时白细胞计数/(×109/L) >30 69(46.94) ≤ 30 78(53.06) 供体类型 亲缘半相合 95(64.63) 亲缘全相合 34(23.13) 非亲缘全相合 18(12.24) 移植物来源 骨髓 9(6.12) 骨髓+外周血 45(30.61) 外周血 93(63.27) TKI类型 伊马替尼 58(39.46) 二代TKI 89(60.54) 移植后TKI维持治疗/月 ≤ 6 33(22.45) >6 114(77.55) 诊断后第90天时分子学水平状态 完全分子学缓解 77(52.38) 部分分子学缓解 49/70(70.00) 无分子学缓解 21/70(30.00) 治疗方案 BU/CY 137(93.20) TBI/CY 10(6.80) MNC计数/(×108/kg) 9.7(2.1~36.8) CD34+计数/(×106/kg) 4.00(1.09~14.30) 表 2 对诊断后第90天CMR状态相关因素的单变量分析

风险因素 P HR(95%CI) 诊断后第90天时CMR状态 BCR/ABL1转录本类型 P190 P210 0.980 1.01(0.47~2.17) 未知 0.810 1.12(0.44~2.86) 染色体核型 单纯Ph+ 合并其他染色体突变 0.768 0.89(0.42~1.88) 未知 0.634 0.74(0.22~2.51) 诊断时白细胞计数≤ 30×109/L 0.171 0.63(0.33~1.22) 年龄≤ 35岁 0.069 0.54(0.28~1.05) TKI类型(一代vs二代) 0.032 0.47(0.24~0.94) 表 3 诊断后90天时达到与未达到CMR患者基线特征

例(%) 类型 诊断后90天时分子学缓解水平 统计量 P CMR(n=77) 未达到CMR(n=70) 年龄/岁 χ2=3.33 0.068 ≤ 35 51(66.23) 36(51.43) >35 26(33.77) 34(48.57) 性别 χ2=0.005 0.826 男 41(53.25) 36(51.43) 女 36(46.75) 34(48.57) 染色体核型 χ2=0.27 0.872 单纯Ph+ 21(27.27) 18(25.71) 合并其他染色体突变 49(63.64) 47(67.14) 未知 7(9.09) 5(7.14) BCR/ABL1转录本类型 χ2=0.06 0.971 P190 46(59.74) 41(58.57) P210 20(25.97) 18(25.71) 未知 11(14.29) 11(15.71) 诊断时白细胞计数/(×109/L) χ2=1.88 0.166 >30 32(41.56) 37(52.86) ≤ 30 45(58.44) 33(47.14) 供体类型 χ2=4.81 0.090 亲缘半相合 47(61.04) 48(68.57) 亲缘全相合 23(29.87) 11(15.71) 非亲缘全相合 7(9.09) 11(15.71) 移植物来源 - 0.761 骨髓 4(5.19) 5(7.14) 骨髓+外周血 22(28.57) 23(32.86) 外周血 51(66.23) 42(60.00) TKI类型 χ2=1.31 0.253 伊马替尼 27(35.06) 31(44.29) 二代TKI 50(64.94) 39(55.71) 移植后TKI维持治疗/月 χ2=0.259 0.611 ≤ 6 16(20.78) 17(24.29) >6 61(79.22) 53(75.71) 治疗方案 χ2=0 1.000 BU/CY 72(93.51) 65(92.86) TBI/CY 5(6.49) 5(7.14) MNC计数(×108/kg) 9.6(3.3~36.8) 9.8(2.1~25.5) Z=-1.03 0.187 CD34+计数(×106/kg) 3.8(1.9~10.1) 6.6(1.8~14.3) Z=-1.56 0.119 表 4 OS、LFS、CIR和NRM相关因素的单变量分析

风险因素 OS LFS CIR NRM P HR(95%CI) P HR(95%CI) P HR(95%CI) P HR(95%CI) 年龄(≥ 35岁vs < 35岁) 0.216 0.59

(0.26~1.36)0.245 0.64

(0.30~1.36)0.919 0.96

(0.42~2.17)0.095 0.27

(0.06~1.26)诊断时白细胞计数(≥ 30× 109/L vs < 30×109/L) 0.429 0.73

(0.33~1.60)0.231 0.64

(0.31~1.32)0.111 0.52

(0.23~1.17)0.703 1.26

(0.38~4.17)诊断后第90天的CMR状况

(是vs否)0.008 3.07

(1.33~7.07)0.001 3.48

(1.62~7.47)0.002 3.95

(1.62~9.62)0.277 2.03

(0.57~7.25)TKI类型(一代vs二代) 0.432 0.71

(0.30~1.67)0.192 0.59

(0.27~1.30)0.297 0.63

(0.26~1.50)0.911 0.92

(0.23~3.68)移植后TKI维持治疗≤ 6个月 0.386 0.67

(0.28~1.64)0.493 0.75

(0.32~1.72)0.719 1.20

(0.44~3.24)0.107 0.37

(0.11~1.24)染色体核型 单纯Ph+ 合并其他染色体突变 0.475 0.72

(0.29~1.78)0.700 0.85

(0.37~1.96)0.704 1.20

(0.46~3.13)0.188 0.38

(0.09~1.60)未知 0.082 3.33

(0.86~12.92)0.064 3.56

(0.93~13.6)0.592 1.52

(0.33~7.12)0.068 4.37

(0.90~21.3)BCR/ABL1转录本类型 P190 P210 0.246 1.71

(0.69~4.27)0.031 2.50

(1.09~5.74)0.049 2.55

(1.01~6.45)0.494 1.59

(0.42~5.99)未知 0.134 2.24

(0.78~6.44)0.055 2.65

(0.98~7.18)0.053 2.92

(0.99~8.63)0.725 1.35

(0.25~7.20)表 5 OS、LFS、CIR和NRM相关因素的多变量分析

风险因素 P HR(95%CI) 风险因素 P HR(95%CI) OS 染色体核型 BCR/ABL1转录本类型 单纯Ph+ P190 合并其他染色体突变 0.345 0.64(0.26~1.61) P210 0.154 2.02(0.77~5.32) 未知 0.084 3.71(0.84~16.45) 未知 0.185 2.21(0.68~7.16) CIR 诊断后第90天分子学水平 BCR/ABL1转录本类型 CMR P190 未达到CMR 0.005 3.59(1.48~8.71) P210 0.063 2.54(0.95~6.80) 染色体核型 未知 0.070 2.89(0.92~9.08) 单纯Ph+ 诊断时白细胞计数/(×109/L) 合并其他染色体突变 0.263 0.57(0.22~1.52) >30 未知 0.106 3.34(0.77~14.46) ≤ 30 0.366 0.67(0.28~1.60) LFS 诊断后第90天分子学水平 BCR/ABL1转录本类型 CMR P190 未达到CMR 0.003 4.00(1.60~9.99) P210 0.016 3.06(1.24~7.57) NRM 未知 0.097 2.70(0.83~8.71) 年龄/岁 TKI类型 ≤ 35 伊马替尼 >35 0.051 0.19(0.04~1.01) 二代TKI 0.996 1.00(0.40~2.49) 染色体核型 诊断后第90天分子学水平 单纯Ph+ CMR 合并其他染色体突变 0.157 0.35(0.08~1.50) 未达到CMR 0.001 4.21(1.84~9.64) 未知 0.048 5.52(1.01~30.06) -

[1] Iacobucci I, Kimura S, Mullighan CG. Biologic and Therapeutic Implications of Genomic Alterations in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia[J]. J Clin Med, 2021, 10(17): 3792. doi: 10.3390/jcm10173792

[2] 中国抗癌协会血液肿瘤专业委员会, 中华医学会血液学分会白血病淋巴瘤学组. 中国成人急性淋巴细胞白血病诊断与治疗指南(2021年版)[J]. 中华血液学杂志, 2021, 42(9): 705-716.

[3] Jabbour E, Haddad FG, Short NJ, et al. Treatment of Adults With Philadelphia Chromosome-Positive Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia-From Intensive Chemotherapy Combinations to Chemotherapy-Free Regimens: A Review[J]. JAMA Oncol, 2022, 8(9): 1340-1348. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.2398

[4] Saleh K, Fernandez A, Pasquier F. Treatment of Philadelphia Chromosome-Positive Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Adults[J]. Cancers(Basel), 2022, 14(7): 1805.

[5] Short NJ, Jabbour E, Sasaki K, et al. Impact of complete molecular response on survival in patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia[J]. Blood, 2016, 128(4): 504-507. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-707562

[6] 中国抗癌协会血液肿瘤专业委员会, 中华医学会血液学分会白血病淋巴瘤学组. 中国成人急性淋巴细胞白血病诊断与治疗指南(2016年版)[J]. 中华血液学志, 2016, 37(10): 837-845.

[7] Chalandon Y, Thomas X, Hayette S, et al. Randomized study of reduced-intensity chemotherapy combined with imatinib in adults with Ph-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia[J]. Blood, 2015, 125(24): 3711-3719. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-627935

[8] Brown PA, Shah B, Advani A, et al. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology[J]. J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 2021, 19(9): 1079-1109. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0042

[9] Kruse A, Abdel-Azim N, Kim HN, et al. Minimal Residual Disease Detection in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2020, 21(3): 1054. doi: 10.3390/ijms21031054

[10] Hovorkova L, Zaliova M, Venn NC, et al. Monitoring of childhood ALL using BCR-ABL1 genomic breakpoints identifies a subgroup with CML-like biology[J]. Blood, 2017, 129(20): 2771-2781. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-11-749978

[11] Colicelli J. ABL tyrosine kinases: evolution of function, regulation, and specificity[J]. Sci Signal, 2010, 3(139): re6.

[12] Dasgupta Y, Koptyra M, Hoser G, et al. Normal ABL1 is a tumor suppressor and therapeutic target in human and mouse leukemias expressing oncogenic ABL1 kinases[J]. Blood, 2016, 127(17): 2131-2143. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-11-681171

[13] Yanada M, Sugiura I, Takeuchi J, et al. Prospective monitoring of BCR-ABL1 transcript levels in patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukaemia undergoing imatinib-combined chemotherapy[J]. Br J Haematol, 2008, 143(4): 503-510. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07377.x

[14] Ravandi F, Jorgensen JL, Thomas DA, et al. Detection of MRD may predict the outcome of patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors plus chemotherapy[J]. Blood, 2013, 122(7): 1214-1221. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-466482

[15] Yoon JH, Yhim HY, Kwak JY, et al. Minimal residual disease-based effect and long-term outcome of first-line dasatinib combined with chemotherapy for adult Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia[J]. Ann Oncol, 2016, 27(6): 1081-1088. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw123

[16] Lee S, Kim DW, Cho BS, et al. Impact of minimal residual disease kinetics during imatinib-based treatment on transplantation outcome in Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia[J]. Leukemia, 2012, 26(11): 2367-2374. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.164

[17] Kim DY, Joo YD, Lim SN, et al. Nilotinib combined with multiagent chemotherapy for newly diagnosed Philadelphia-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia[J]. Blood, 2015, 126(6): 746-756. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-636548

[18] Ghobadi A, Slade M, Kantarjian H, et al. The role of allogeneic transplant for adult Ph+ ALL in CR1 with complete molecular remission: a retrospective analysis[J]. Blood, 2022, 140(20): 2101-2112. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022016194

[19] Alousi A, Wang T, Hemmer MT, et al. Peripheral Blood versus Bone Marrow from Unrelated Donors: Bone marrow Allografts Have Improved Long-term Overall and Graft-versus-Host Disease-Free, Relapse-Free Survival[J]. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2019, 25(2): 270-278. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.09.004

[20] Gökbuget N, Hoelzer D. Treatment of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia[J]. Semin Hematol, 2009, 46(1): 64-75. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2008.09.003

[21] Thompson JA, Schneider BJ, Brahmer J, et al. Management of Immunotherapy-Related Toxicities, Version 1.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology[J]. J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 2022, 20(4): 387-405. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2022.0020

[22] Chiaretti S, Ansuinelli M, Vitale A, et al. A multicenter total therapy strategy for de novo adult Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients: final results of the GIMEMA LAL1509 protocol[J]. Haematologica, 2021, 106(7): 1828-1838. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2020.260935

[23] Sugiura I, Doki N, Hata T, et al. Dasatinib-based 2-step induction for adults with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia[J]. Blood Adv, 2022, 6(2): 624-636. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004607

[24] Lv M, Liu L, He Y, et al. Outcomes of allogeneic or autologous stem cell transplantation followed by maintenance chemotherapy in adult patient with B-ALL in CR1 with no detectable minimal residual disease[J]. Br J Haematol, 2023, 202(2): 369-378. doi: 10.1111/bjh.18846

[25] Lyu M, Jiang E, He Y, et al. Comparison of autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantation for patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia[J]. Hematology, 2021, 26(1): 65-74. doi: 10.1080/16078454.2020.1868783

-

计量

- 文章访问数: 62

- 施引文献: 0

下载:

下载: